Volgonsi i secoli, danzano l’ombre, il colmo cade e il fondo rialza. Balena il vespero dei prigionieri, dita rosate su falci e memorie. Tu vago vaghi viandante di vuoto, nella canicola l’aria accecata. Cenci di brume sia sopra che sotto, guizzi d’eterno poi stilla la notte. Cinque è il quadrato e tredici otto, torna nel sogno all’anime rotte.

Articolo in Italiano

: Venere e il Priaforà

: Venere e il Priaforà

Truthfully, a sight or a photo are but particular coincidences: unaware photons traveling to unknown directions, caught and bent by an optical alchemy, left an electrochemical impression, a memory of their past existence.

I witnessed many of these coincidences and there is a record of several of them on this website. The opening picture shows Venus, in its phase as evening star, as it crosses the natural arch of Mount Priaforà, on February 16th. Sometimes coincidences happen by chance or sheer luck, and in those occasions who experience them is astonished and impressed. But other times, they instead need to be sought and created; this post summarizes my quest for the perfect passage.

the Idea to take a picture of Venus while floating in the hole of Priaforà came from my previous observations of the passages of the Sun, the Moon and Jupiter. I shot a picture of the latter almost 10 years ago, thanks to a fortuitous sight during an agitated night; back then, I made some trigonometry to find the spot where I should have set-up the camera, but I had to correct it last minute because the uncertainty in the determined positions was too large. From night to night the position of Venus in the sky can change much faster than the one of Jupiter (because Venus is closer to the Sun and moves faster), and to get a glimpse of its beautiful phase through the mountain’s hole a lightweight and portable telephoto lens would have not been sufficient. I should have looked for much more precise positions than those of Google maps to calculate precisely the place to set up the telescope…

the Hike. Beimg so, the first step was to precisely determine the geographical coordinates of the buso (hole) of Priaforà. Assisted by this year’s abnormally warm winter, it was not hard to face five hours of trek to reach the natural arch. And it was really worth it: it was a splendid hike!

For those of you who are curious about the mountain: Priaforà can be easily reached from the nearby Mount Novegno through the Campedello pass. Nevertheless, we Velesi are used to follow the paths that were made by the lumberjacks in the past, and that roam far and wide through the vast woods thriving on the slopes of the mountain. I hiked up together with my friend Omar following the path of the “tre bocchette” from the “Sojo Prasalbo”, a steep but panoramic trail. Please do not underestimate the risks that even lower heights like Priaforà (1659 meters above sea level) may pose; unfortunately even on this mountain there was a fatal accident some years ago.

Once I got to the buso, I used the GPS receiver of my phone to get its exact position with a free and open-source program: GPSLogger. The app has many configuration options, and once started it saves a track in three different formats: GPX, KML (Google Earth) and simple CSV. Just to be on the safe side, before starting the data acquisition I re-calibrated the integrated compass of the phone with the ancient program Sky Map (former Google Sky Map), and I cross-checked the quality of signal reception with GPS Cockpit. This latter check made me realize an important factor, that I discuss in the coming paragraph. To actually get the data, I started the track recording, waited for the position accuracy to stabilize, and recorded positions for few minutes while moving a little bit within the few meters that span the hole in the rock. Later, I used the average of all of these points as the coordinates of the natural arch:

But the result was odd. An elevation of 1637 meters is just 22 meters lower than the mountain summit, but the highest point rises quite a bit more above the natural arch. And the GPS Cockpit gave instead an instantaneous reading of 1589 meters. What was happening? Where did this difference come from? Who had added 50 meters to the mountain?

the Geoid. Leaving aside malevolent and aberrant conspiracy theories in the obscene dumpster where they deserve to be abandoned, it shouldn’t surprise anyone that the Earth hasn’t got a precise geometric shape. More so, it shouldn’t even make as a great discussion topic, it is a trivial fact! The shape of the Earth is undefined and undefinable: after all, what geometric shape do a cat, a stone or a wave possess? Aren’t perhaps the cat, the stone and the wave part of the Earth? The spherical approximation is excellent and valid for nearly all simple calculations one might want to think at. It needs to be replaced with something better only when dealing with exquisitely geographical matters. A certain guy with Modenese ancestry (from mother’s side) tells me that even during the genesis a well-known rogue one notices that the world is all flattened on its poles [t.n. the reference here is to a somewhat lesser-known comic song of Italian songwriter Francesco Guccini. The song re-imagines a tale of the genesis in which a bored god created the universe by mistake, trying to invent television instead.]. The reference ellipsoid WGS84 is the most used of such models that account for polar flattening, as it is at the base of the GPS coordinate system. The difference between the polar and equatorial radius amounts to roughly 21 km, or 0.3%. However, not even the WGS84 can catch the essence of Earth’s shape, simply because Earth doesn’t have one such shape! And if it had one, it would change each time you squat to tie up your shoes, or when a leaf falls! Being so, let’s call it a day and just refer the coordinates to the WGS84 ellipsoid, which is what navigation satellites do too.

Still, if the ellipsoid does the job for latitude and longitude, elevation is a whole other story. We are used to refer it to the sea level… but even if this was not affected continuously by waves and tides, what exactly is the sea level for something atop a mountain? The geoid is an attempt at answering this question. The geoid is the realization of an imaginary equipotential surface, defined in such a way that it deviates minimally from the mean sea level. In other words: if water were a magical fluid without any mass or substance, permeating the world and unaffected by waves and tides, then the surface of this impalpable ocean would match the one of the geoid, and on it the gravitational potential energy of the Earth would be constant. The geoid is not the shape of the Earth, as some pedant ones reply on reddit to some other insane ones, but a model of its gravity and centrifugal force. The local height of the geoid on a point of the Earth can depart from the WGS84 ellipsoid in a range of plus or minus one hundred meters; these correspond to 0.5% of the polar flattening already corrected by the ellipsoid, and 0.001% of the Earth radius.

Well, on the entire western Europe the geoid is above the reference ellipsoid: that is, the undulation of the geoid is positive, and close to the Alps it is even slightly higher, for the great mass of the mountain chain locally modifies the strength of gravity. On Mt. Priaforà and surrounding areas the geoid height over the WGS84 is roughly 48.5 meters. By subtracting this value from the WGS84 elevation measured with the GPS we can recover the real elevation above sea level of the natural arch of Priaforà: 1589.5 meters, seventy meters below the summit.

the Fields. The magical journey on the ellipsoidal versus geoid height had given me a valuable insight: I couldn’t trust data on maps and charts for my geodesic exercise: what were those elevations calculated from, a reference ellipsoid or a geoid? When had they been sampled? Using what reference? I needed a grid of accurate positions around my place to hope and spot the exact location where I would have had to setup the telescope. The resolution of Google maps and similar software is too coarse to get something good out of them, and I’ve had a proof of this when I took the time-lapse of Jupiter. I couldn’t think of any solution other than sampling by myself the landscape where I was raised, using again the phone and its GPS receiver.

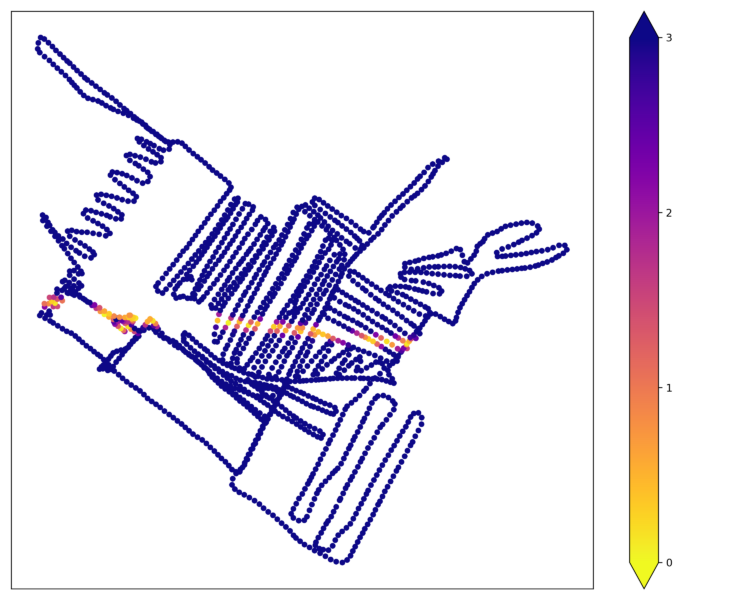

Therefore, I proceeded and walked around far and wide on nearby fields and meadows for a good hour and a half, leaving back a trail of GPS points every three seconds. I was never more than 300 meters from my own house, but I walked for six kilometers, the mind continuously going back to Peano’s curve. The picture here above represents the path I’ve made, where the space between each dot depends on the exact speed I kept while walking. Have you ever seen such a monstrosity of a GPS track? Just as before, I had to exclude the first data-points as well, those taken just after switching on the phone GPS, as they weren’t accurate enough.

the Numbers. Once the data had been taken, I had to transform them into something useful. Since I basically read and code in python even while sleeping (the left and right hemispheres have not yet reached an agreement on what version to use), it was nearly natural to me to code up a small script to get the information I needed. The script performs these operations:

- Reading the track obtained at the buso (through the CSV file from GPSLogger, with pandas) and averaging the multiple determinations of the coordinates.

- Transforming WGS84 latitude, longitude and elevation in ECEF coordinates (Earth-Centered-Earth-Fixed), a Cartesian reference frame with the origin at Earth’s center and fixed on it, in units of meters. This step is required to carry on more easily with the following one. This transformation was done with a function from the pyproj package.

- Calculating the azimuth and altitude of the natural arch as seen from each position sampled on the fields. Originally I though of employing a rotation matrix over the ECEF coordinates of these, but I later found a pre-cooked function in the pymap3d package. At this stage, the alt-azimuth coordinates of the target are known, as well as its line-of-sight distance from every possible observation site.

- The real search for Venus passages begins; to do so, I heavily relied on the excellent skyfield library by B. Rhodes. First, the program searches with a coarse resolution the time of closest conjunction between Venus and the mountain’s hole, as seen from a reference midpoint, roughly the mean of all the other possible sites. The calculation is repeated for twenty days during February, obtaining a reference time series for each evening. These closest conjunction times won’t be used in the following calculations, but for determining a time span of half an hour (plus and minus fifteen minutes) to be used to conduct a more precise search.

- Within this time interval, the algorithm calculated for every sampled position the apparent position of Venus and determines its angular distance from the hole, as seen from that particular position. The computation is iterated for every second in the half-an-hour time span; the separation between Venus and the Priaforà is therefore computed 1800 times (half an hour) for each of the roughly 1800 positions, and for 20 days: 1800×1800×20 ≃ 65 million times!

- The data are saved on disk. Although there are very efficient file formats for this kind of data, I decided to save them as simple yaml files. This is because the yaml format can easily be read by a person, rendering the initial debug particularly simple. The data of the closest conjunction in each evening is also added as a file header:

#out_16.yaml

#closest conjunction at 0.0012 on index (np.int64(591), np.int64(1126)).

#point -0.0008022388888863372, 0.0016091022222226034, 344.94.

#time 2025-02-16T18:40:18.465Z. - The resulting datasets can be represented by another couple of scripts, that produce a graph of the minimum separation as seen from each of the positions on the ground or a video of how this varies with time. One such plot is shown in the previous figure, with the color scale describing the minimum separation in arc-minutes.

As the hole in the rock has a maximum diameter of about three meters and it is at roughly 4.3 km of radial distance away from the observation sites, its apparent angular diameter is barely larger than two arc-minutes. As a consequence, its projection on the ground, or its “shade” if you prefer, is very narrow and a displacement of few meters is enough to miss it. After crunching up all these numbers, a question was still lingering: would it have been sufficient to locate the correct place to be at, for Venus to cross the arch?

Bellatrix. But I had a card up my sleeve. I know a star that, when observed from the right window, sets through the buso of Priaforà, every day. And it is no dim star, but Bellatrix, the warrior star on Orion’s shoulder, among the thirty brightest stars of the sky! So I stood up until 1 AM to time its passage; I barely succeeded due to thick mists. The calculation foresaw that from that spot and at that time the conjunction would have been 1 arc-minute wide, providing a good confirmation to the accuracy of the program.

It was around that day that the weather started getting worse. Moreover for my job as a researcher I live in Germany, and I can reach back home only during weekends. Clouds hid any further possible observation until Friday 14th. It rained all day, but half an hour before the predicted time, the sky opened up a little while. Given the very favorable position for the observation, I prepared a tripod with a tele-photo lens. Unfortunately, mists got thicker just before the right time, but photos still showed an extremely feeble trace of the passage…

the Gear. On February 15th the sky was glorious and clear. In late afternoon, full of hopes, I started to prepare the instruments. I chose a Mak-Cassegrain telescope with a focal length of 1300 mm and a focal ratio of f/10 to try and catch a close-up view of the phase of Venus, using my 60Da camera (APS format). In parallel, I mounted a heavy but well-built 400 mm, f/4 refractor, to get a larger and faster field of view with the full-frame Z7. Finally, on the easily movable tripod I left my oldest camera, the 1000D, with a 300 mm, f/5.6 tele-photo lens. I reasoned that, if I had realized last minute that I had gotten the position wrong, I could have at least tried to quickly move the tripod and get a nice sequence with the old 1000D.

To refine the position, I took another GPS track around the predicted spot for 15 minutes, confirming the central line where I should have set-up the ‘scopes. Everything was ready, and I took some pictures of the mountain to use them later for the composition. And then… the usual playful chaos of weather wanted to have its saying in the whole thing last moment. Humidity, that had rose from the ground during the day, condensed back as soon as night fell, and the mountain cloaked itself in an unfathomable and impenetrable cape of clouds. I had done everything for nothing.

the right Time. Devoid of hopes, on the next day I set up everything again. According to my calculations, if on February 14th the passage had happened essentially right up my door, and on 15th I had to move everything by roughly 100 meters, on February 16th I would have had to slide 75 meters further away, amid a muddy and bogged down field that I had included in my sampling just because “one never knows”. The weather was rather variable and it switched between clearings and clouds for the entire day. I began setting up all the gear three hours ahead of time, in a sort of dreamy lethargy, a preemptive defense shield against another probable disappointment.

But there’s a thing I’ve learned in these years gazing the heavens as a passion and profession. All the work we do for a project, all the buzzing around to reach an objective, all that pondering on an important choice, all the hope that keeps us fighting for a dream, all of this… is not all that matters. Luck, chance, chaos and the unforeseen equally contribute in every aspect of existence, if not more, than all our work. On the one hand, this can seem distressing, but from another perspective it is, frankly, a liberation.

Well, this time chaos gave me a chance, and my work had been good, because the passage of Venus in the buso of Priaforà showed itself clear and beautiful as I had imagined, and exactly from the spot I had chosen.

All three cameras recorded it, even the smaller one I had displaced by a couple of meters to cover a larger possible area. But in those moments, all the beauty and joy were for our very own pupils, gazing into that mysterious and ancient, benevolent eye, suddenly enlightened, with blazing reflections on the snow and its rocky arch…

La pietra antica non emette suono,

o parla come il mondo, come il sole,

parole troppo grandi per un uomo…

[n.t. The ancient stone does not emit a sound; or maybe speaks as the world, as the sun do; in words far too great for a man… This is another reference to Francesco Guccini’s work. The song it comes from is “Radici” from the album bearing the same name.]

at the Computer. As often happens, but nobody usually goes through the hassle of telling, the adventure does not end with happy me in a field covered in mud and the dazzling sight of the evening star, at its maximum splendor, through the eye of Monte Priaforà. It ends in the following hours and days working at the computer, processing the photos, stacking the two compositions, and building the time-lapse video that you can see here. And, if I may say so, it ends a bit also writing this post.

This little but sweet extravaganza kept me busy for almost a month, and it was all over in less than ten seconds. But I am happy with the result. Walking and hiking, but also going around in my car, for a little while I won’t help but imagine myself moving in the three dimensions, as if I was a bird always flying close to the ground. Writing this summary on the website took more than the time I spent to write all other posts of the last ten years. I hope you enjoyed it, and if it is so, please leave me a comment… so that at least I know somebody read it! 🙂

I translated this post in English without using any machine translator or AI. As such, there might be typos, or some sentences might sound off. If you spot such mistakes, please tell me, I’ll correct them.

I wish you all a favorable orbit, and good luck in the search for you own, very personal, conjunctions.